Big questions: What is genetically determined, and how?

Contents

2.1. Big questions: What is genetically determined, and how?¶

As humans, we are curious and want to understand ourselves. We want to know the answers to questions like: “Why are people the way we are?”, “Which aspects of ourselves have we inherited?”, and “What is fixed and what can be changed by the way we live our lives?” Looking at what we are made from - more specifically the DNA that can be found in each of our cells - has promised answers to some of these questions.

We ask so many questions, not only out of curiosity, but also in order to improve and control our lives and environment. This drive for control hasn’t always been a good thing: in recent history, genetics has been used to justify extremely harmful and unethical racist eugenics policies. While eugenics is thankfully no longer in vogue, there is no guarantee that scientific knowledge will be used ethically. Modern-day genetics still raises concerns about which of our traits should be medicalised or pathologised: should we be looking for cures for autism if autistic people don’t want them?

However, knowing more about ourselves clearly also has the capacity to be used for the good of all. By understanding how our bodies work, researchers seek to develop new, more effective, and kinder treatments for diseases. Alongside curiosity, these were my aims in seeking to explore the molecular link between genotype and phenotype.

2.1.1. History of inheritable traits¶

Humanity has been trying to answer the big questions long before we discovered DNA. The ancient theory of soft inheritance[11] said that people can pass on traits they gained during their lives, while 16th-century alchemists theorised that sperm contains tiny fully formed humans[12] (i.e. women didn’t pass down anything).

In 1859, Charles Darwin published his book On the Origin of Species[13], explaining his theory of natural selection: organisms compete for resources and not all can survive to reproduce, some organisms will have traits that increase their chances of this, and those that do pass on their traits to the next generation. The theory predicts and explains the gradual change of heritable characteristics over time: evolution. Darwin presented homologous anatomical structures, like the similarity between a bat’s wing and a human hand, as evidence for evolution and shared ancestry.

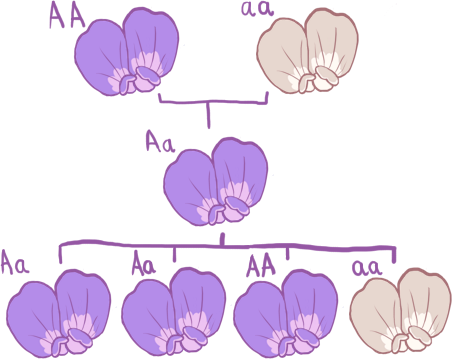

Fig. 2.1 An example of Mendel’s experimental results, for white and purple pea flowers. He began with “pure line” pea plants (which always produced self-identical plants when self-pollinated). Crossing the “pure line” plants resulted in first generation offspring which always had purple flowers. When self-pollinated, these first generation plants created plants with purple and white flowers in a 3:1 ratio.¶

Inspired by Darwin[14], his contemporary Gregor Mendel’s famous pea experiments[15] provided the earliest scientific basis for genetics through his experiments with independently inherited traits of peas (e.g. purple or white flowers, tall or shot plants, wrinkled or round seeds…). Importantly, he discovered rules of inheritance that indicated that offspring have combinations of discrete genetic material (rather than a blend), i.e. we don’t see pink flowers when we cross purple and white flowered peas. He also showed that single traits (e.g. purple flowers) can actually be caused by different underlying genetics (see Fig. 2.1).

This concept was expanded by Wilhelm Johannsen, who coined the term “gene” as the name for the hidden material that caused the traits. Johnannsen’s work also distinguished between “genotype” and “phenotype”: genotype being the hidden (genetic) material that organisms have, and phenotype being the measurable trait[16]. His research showed that some phenotypes (e.g. seed size) could vary considerably even with genetically identical plants, due to their environment.

Phenotypes are not only strictly Mendelian, with a fixed number of “types”, or continuous and without a genetic basis. Ronald Fischer showed that variation in continuous traits (such as height in humans) can be consistent with Mendelian inheritance if multiple genes contributed additively to the trait. Many traits are complex in this way, meaning that they are influenced by many different genetic factors, as well as the environment.

When Watson and Crick discovered the now familiar structure of DNA in 1953[18], we took a huge step towards being able to answer our big questions. We finally understood the molecular structure that underlies inherent traits. Then in 2003, with the completion of the Human Genome Project[19], it was possible to read the human version of this “code of life”. Once researchers had access to the whole genetic code for a person, they could set about trying to decode it, with the world hoping that this landmark would aid the search for treatments for diseases like cancers and Alzheimer’s[20].

We now have thousands of human genomes to investigate. As I will explain, this enables the computational predictive methods that enable any characterisation of protein function for the majority of proteins, since the cost of alternative investigation of our complex network of proteins remains prohibitive.

The promises of gene therapies and personalised medicine are now beginning to become reality, due in part to computational biology and bioinformatics breakthroughs. At the time of writing, there are eleven cell and gene therapies approved by the European Medicines Agency[22], which treat a variety of cancers, as well as Crohn’s disease, and eye and cartilage problems. In addition, the first personalised genomic medicine chemotherapy treatment is now available on the NHS, for cancer patients with the allele of the DYPD gene that cause slower breakdown of chemotherapy toxins[23].