Looking more closely at proteins: function, structure and classification

Contents

2.4. Looking more closely at proteins: function, structure and classification¶

Just as DNA has been classified at different levels (SNP, gene, genome), so too have proteins. In contrast to DNA, what’s interesting (and useful!) to know about proteins is their structure.

As mentioned earlier, translated strings of amino acids fold automatically (or sometimes with the help of other proteins) into the 3D structure of proteins. This structure defines what molecules (large and small) they can bind to, and this has huge consequences for their functionality in the body. Moreover, proteins have recognisable features of their structure which appear again and again. These features occur at different levels and sizes, and they allow us to learn about the evolution and functional similarity of proteins.

2.4.1. Protein structure: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary, and Quaternary¶

Proteins are described and classified in terms of the their primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure.

The primary structure is simply the amino acid makeup of the protein, which describes the protein’s chemical makeup, but not it’s three-dimensional structure. These amino acid strings tend to form into a small number of familiar (secondary) three-dimensional structures, for example beta strands, beta sheets, and alpha helices. At the next level, the tertiary structure describes combinations of secondary structures, for example a TIM barrels (a torroidal structure made up of alpha helices and beta strands). At this level, similar structures do not imply an evolutionary or functional similarity.

2.4.1.1. Quaternary structures: protein domains¶

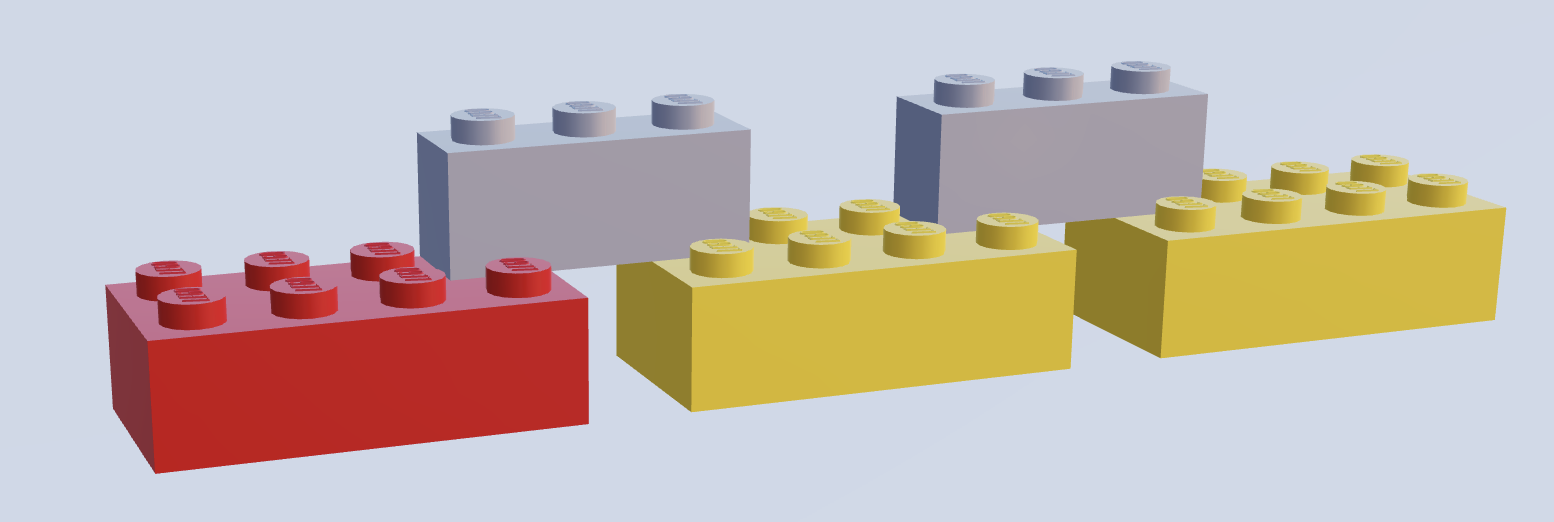

Fig. 2.5 An illustration of the lego analogy for protein domains. Coloured bricks represent protein domains - colour represents a specific protein domain type, while thin grey bricks represent polypeptide linkers which link domains. Image created using mecabricks[37]¶

The quaternary structures of proteins - protein domains - have proved particularly interesting for research. A simple and oft-used metaphor is to think of protein domains as lego building blocks (Fig. 2.5) which can be linked by polypeptide chains to make up a protein. These polypeptide chains (known as linkers) are often inflexible, in order to allow only one conformation of the protein. Small and simple proteins often consist of just one domain, while bigger proteins can contain many domains. An individual domain can be found in many different proteins, and multiple times in the same protein.

Protein domains are interesting because they are highly conserved in evolution, and are thought of as units of function, evolution, and/or structure. The functions of proteins, at both low-level (e.g. “calcium signalling protein”) and high-level (e.g. involved in “liver disease”), are costly and difficult to discern, so there are many proteins about which little is known. For this reason, often proteins are classified according to their similarity to proteins about which functions are known, for example those containing the same protein domains.

2.4.1.2. Disorder¶

While protein domains always exist in one conformation, this is not the case for proteins as a whole. One reason for this is that not all linkers are rigid. Flexible regions of proteins which allow for various conformations are referred to as disordered.

And disordered regions are not only relegated to linkers between domains. Proteins can be constituted entirely of disordered regions, or may have large disordered regions.

Such intrinsically disordered proteins can exist in a number of conformations, rather than one fixed structure. On some occasions, the disordered regions are known to be functional, while on others, proteins may be non-functional until they bind with another macromolecule which forces them into a fixed conformation.

2.4.1.3. Classifying proteins by domain: families and superfamilies¶

Proteins with known domain structure can be grouped together based on their structural similarities, based on the consideration of the protein’s constituent domains into families, superfamilies and folds. Proteins are classified into families representing the most similar proteins, which share a clear evolutionary relationship, while superfamilies represent less close evolutionary relationships, and folds represent the same secondary structure. This protein classification task, while aided by automation, was carried out largely by manual visual inspection[38].