Biological molecules: DNA, RNA, Proteins and the central dogma of molecular biology.

Contents

2.2. Biological molecules: DNA, RNA, Proteins and the central dogma of molecular biology.¶

Here I introduce the classes of biological molecules that are vital in our understanding of genetics: the nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), and their product: proteins.

2.2.1. DNA¶

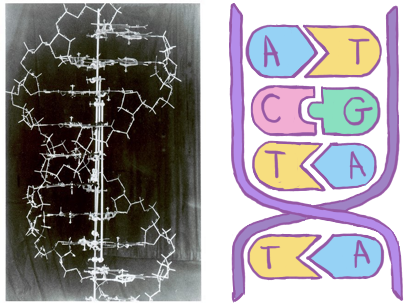

Fig. 2.2 Left: A photo of the original six-foot tall metal model of DNA made by Watson and Crick in 1953, alongside their discovery[18]. Image from the Cold Spring Harbor Archives[24]. Right: A cartoon representation of DNA, showing the concept of the complementary strand.¶

Most people recognise the double helix of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) shown in Fig. 2.2, it’s a twisted ladder consisting of four nucleotides; adenine, cytosine, thymine, and guanine (A, C, T, G). Its the “code of life” that contains the instructions for making (almost) all of the things which make up our bodies and therefore, an obvious starting point for understanding how they work. A given nucleotide on one strand is always linked to its partner on the other strand - A with T, and G with C - which creates redundancy and a convenient copying mechanism. Lengths of DNA are measured in these base pairs (bp).

Human DNA is organised into chromosomes, we have two copies of each of our 23 nuclear chromosomes within (almost) every cell, as well as a varying number of copies of our mitochondrial chromosome in the cells which have mitochondria.

2.2.1.1. How DNA affects us: the central dogma of molecular biology¶

The way in which DNA affects the body can be understood through the central dogma of molecular biology, and in doing so we will also become acquainted with two more important biological molecules: RNA and proteins.

The central dogma of molecular biology can be paraphrased as “DNA makes RNA makes proteins”. The idea is that as the “code of life”, DNA contains the instructions for making RNA, which contains the instructions for making proteins, and proteins are the molecules which constitute and make up almost everything in our bodies.

The central dogma is a description of the process of gene expression. Gene expression has two parts: transcription (“DNA makes RNA”) and translation (“RNA makes proteins”). By looking at these mechanisms we can gain an appreciation for the role of DNA in gene expression, and in phenotype.

2.2.1.2. “DNA makes RNA”, a.k.a, transcription¶

RNA (or ribonucleic acid) was originally discovered alongside DNA as a nucleic acid, an acidic substance found in the nucleus of cells, hence it’s similar name. It was later discovered that they are also found in bacterial and archeal cells (which don’t have nuclei). In contrast to DNA, RNA is a single-stranded molecule, with the bases A, C, G and U (i.e. uracil instead of thymine), and with a different backbone (containing ribose, rather than dioxyribose). There are different forms of RNA which perform different functions. It is messenger RNA (mRNA) that is the intermediate product between DNA and Proteins.

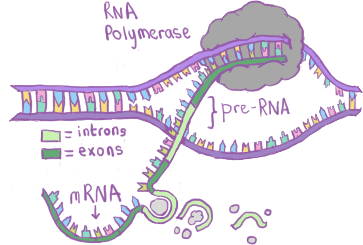

Fig. 2.3 An illustration of the transcription and splicing processes, showing the role of RNA polymerase in building RNA.¶

The process by which “DNA makes RNA” is known as transcription. The process happens to certain lengths of DNA, and these lengths of DNA are which are called genes. In humans, genes vary in length from hundreds to millions of base pairs.

The action of transcription is largely carried out by an enzyme called RNA polymerase, which binds to a promoter region of the DNA, close to but outside the gene. This region is only accessible in certain cellular conditions. A rough model is that in conditions in which it is unfavourable for the gene to be transcribed, other molecules will block the promoter.

Fig. 2.3 illustrates the next part of this process. The RNA polymerase splits the DNA and adds complementary RNA nucleotides to the DNA, after which the RNA sugar backbone is formed. The RNA-DNA helix is then split, at which point we have what is known as precursor RNA or pre-RNA.

After transcription, the pre-RNA then undergoes post-transcriptional modifications such as splicing, where parts of the RNA (introns) are removed, leaving only exons. This can also bee seen in Fig. 2.3. Splicing is part of the final processing step to create the finished product: a mature RNA transcript.

During this step a gene could be transcribed into one of multiple transcripts, via a process known as alternative splicing. This can happen, for example, by skipping some of the exons during splicing. So, a more accurate statement is “DNA makes RNAs”: there’s not a one-to-one relationship between genes and transcripts, and therefore the same is true between genes and proteins. These different but related versions of proteins which come from the same gene are known as protein isoforms.

Other post-transcriptional modifications can also affect transcription and therefore human disease. Two key such modifications are RNA interference (RNAi) and RNA editing. RNAi relates to the degradation of mRNA before translation - this mechanism has been used to successfully create several drugs such as Givosiran which is used to treat rare metabolic diseases. Meanwhile RNA editing relates to all types of RNAs being edited after transcription - these modifications have also been linked to disease[25].

What is transcribed and how quickly is affected by many different kinds of proteins, as well as other molecules, through epigenetic modifications. Transcription factors are of particular note. These are proteins that bind to DNA close to or in a nearby promoter region, and either activate the gene (increasing it’s rate of transcription), by for example recruiting RNA polymerase, or repress it (decrease it’s rate of transcription). These transcription factors are in turn regulated by other transcription factors, which creates a network of gene regulation; a gene regulatory network (GRN).

2.2.1.3. “RNA makes Proteins”, a.k.a. Translation¶

The second part of the central dogma is “RNA makes proteins” a.k.a. translation.

Proteins were discovered independently from DNA and RNA. They were named by Dutch chemist Gerardus Mulder in his 1839 paper[26], where he found that all proteins from animals and plants have more or less the same elemental makeup - approximately C400H620N100O120. This intriguing result bolstered research in this area, eventually resulting in our current understanding of proteins as biological macromolecules composed of amino acids.

The fact that the sequence of amino acids was a code which precisely determined the three-dimensional structure of proteins was discovered by Christian Anfinsen for which he was awarded the 1972 Nobel Prize. This was achieved through a series of experiments, which for example, showed that a protein could be reduced to a string of amino acids, and then in the right conditions could refold to the exact original protein structure[27,28].

Translation describes the process in which a string of amino acids is created based on the RNA sequence. Proteins are made of these amino acid strings (called polypeptides), and after translation, they will fold (potentially with the assistence of chaperone proteins) into the proteins usual globular three dimensional conformation.

Fig. 2.4 Left: An amino acid wheel chart showing the mapping between nucleotide codons of RNA and amino acids. The chart is read from the inside out, for example UGA is a stop codon and UUG encodes for leucine “Leu”). Right: An illustration of the translation process, showing tRNAs delivering amino acids to the ribosome in order to build the polypeptide chain which makes up proteins.¶

Translation is mostly carried out by a large and complex piece of molecular machinery called the ribosome, which is made up of proteins and ribosomal RNA (rRNA). The ribosome reads and processes RNA in sets of three nucleotides at a time - these are called codons. Each codon is either a flag to the ribosome (e.g “stop here”, “start here”) or corresponds to an amino acid. Transfer RNA (tRNA) transports the amino acids to the ribosome where the polypeptide chain of amino acids is created.

Although we would expect \(4^3=64\) permutations of nucleotides, there are only 21 different amino acids which can be incorporated into proteins in humans, so there is redundancy: multiple codons can encode for the same amino acids. We can see this clearly in the left part of Fig. 2.4, for example, UAA, UGA, and UAG are all read as stop codons. Different codons are not necessarily entirely equivalent, however, they can cause different patterns of expression due to being translated at different speeds.

Amino acid strings then fold reliably into 3-dimensional protein structures, sometimes with the help of other “chaperone” proteins. Despite all science has long known about the chemistry governing the folding of amino acid chains, we could not predict this very well until very recently.

After translation, and either before or after folding[30], proteins can also be subject to post translational modifications. These changes consist of chemicals bonding to the protein, which can for example change its function or structure, assist in folding, or target them for degradation.

The process of translating mRNAs can be repressed by very short RNAs called microRNAs (miRNAs) that can bind to more than half of mammalian mRNAs[31].

2.2.1.4. “… and proteins do everything.”¶

The unwritten addendum implied by “DNA makes RNA makes proteins” is “…and proteins do (almost) everything”. If DNA is the blueprint for life, then proteins are what make up life. They are the material building blocks of our bodies, and they also have a vast number of other functions: they can be enzymes catalysing reactions, hormones controlling metabolism, transporters for other proteins, signalling proteins, they might be transcription factors (controlling the expression of genes), or have many other functions.

In turn, these processes influence our phenotypes. A phenotype can be something like the level of a certain hormone in the bloodstream, so in a very simple case, a different amino acid in a hormone protein could cause the protein to be expressed or function differently. A phenotype could alternatively be something like height, which could have a number of genetic (and non-genetic) influences.