Ontologies

Contents

3.3. Ontologies¶

Fig. 3.3 Carl Linneaus developed a system of classifying plants, animals and minerals, including plant classification based on their number of stamens[100]. The left image is a key to this classification system taken from his book, while the right image is a depiction of how the system works, drawn by botanist George Ehret[101].¶

Cataloguing and classifying has been a successful scientific endeavour in other disciplines (e.g. the periodic table), but it’s a cornerstone of biology. Biological classification dates back to the Linnaean taxonomy from the mid 1700s (see Fig. 3.3), which described species, their features, and the relationships between them[103]. It also contained some hateful racist ideas. Nonetheless the idea of measuring and categorising the biological world also birthed an enduring tradition of classification in biology, which have led to some of it’s most important discoveries.

Modern biology continues in this tradition of classification, cataloguing biology in ever more (molecular) detail: cells, genes, transcripts, proteins, and pathways. One major way in which this data is synthesised is through the use of ontologies.

3.3.1. What are ontologies?¶

Ontologies are a way of organising all of the information we have collected in classifying and annotating biological concepts and entities, into a unified framework: one which we can represent, build, and query computationally. Biological ontologies represent knowledge that we have about the relationships between biological entities. Ontologies have classes (called terms), which are organised in hierarchies, i.e. such that a term can be a subclass of another. For example, in an ontology of anatomy, we could see that the left heart ventricle is an example of a heart ventricle, which is part of the heart. And more distantly, the left heart ventricle is part of an organ.

There are ontologies organising all kinds of biological concepts: a number of ontologies that contain anatomical entities (like the heart example) for individual species, ontologies for molecular function, biological processes, diseases, cellular components, etc.

What they have in common is that they organise entities through names, descriptions, and IDs, and relate these classifications to one another hierarchically, sometimes with multiple types of relationships (e.g is_a, part_of).

The hierarchy of ontologies can be thought of as having a tree-like structure with one, or just a few root terms which are very general terms that all other terms in the ontology are related to, for example biological process, and leaf terms, which are the most specific terms in the ontology (e.g positive regulation of cardiac muscle tissue regeneration).

Relations between terms are directional, for example positive regulation of cardiac muscle tissue regeneration is a regulation of cardiac muscle tissue regeneration, but not vice versa.

In such relationships, we say the parent term is the more general term closer to the root (e.g. “positive regulation of…”) and the child term is the more specific term (“regulation of..”).

It is not permitted for there to be cycles in ontologies, for example term A is_a term B is_a term A: ontologies are often DAGs (Directed Acyclic Graphs).

Ontology term identifiers are usually of the form: XXX:#######, where XXX is an upper-case identifier for the whole ontology, e.g. GO for Gene Ontology, CL for Cell Ontology, etc. For example, GO:0008150 is the GO term for Biological Process.

Some ontologies also include annotations: these relate the terms to other types of information. In the Gene Ontology, there are annotations which relate gene functionality to genes, for example. There can also be annotations linking to publications from which the knowledge about the term was obtained.

Ontologies summary

Ontologies:

Organise information about terms into a framework, with relationships between them.

Organise terms hierarchically, into Directed Acyclic Graphs, such that there are more specific child terms which are subclasses of more general parent terms.

Have a tree-like structure with the most general terms being the root and the most specific being the leaves.

Allow entities (terms) to be annotated with additional information, e.g. annotating gene functions to genes.

3.3.2. How are ontologies created, maintained, and improved?¶

Biological ontologies are generally created through some combination of manual curation by highly skilled bio-curators and logic-testing (checking for illogical relationships, for example using ROBOT[104]). Creating an ontology is generally a long-term project, with new suggestions and updates to the ontologies being made as new knowledge accumulates, or just as more people have time to add to them. As well as being the work of dedicated curators, contributions to ontologies can usually be crowd-sourced from the scientific community using GitHub issues, mailing list discussions, web forms, and dedicated workshops. In this way, they are similar to other bioinformatics community-driven efforts like structural and sequence databases.

Since they are time-consuming to produce and require such expertise, successful ontologies tend to have (or at least begin with) a quite specific scope, for example the anatomy of a zebrafish. However, there are also cross-ontology mappings and annotations, where terms from one ontology are linked to those in another (e.g. relating gene functions and tissues) or to entities in a database (e.g. gene functions to genes). These also require the work of dedicated curators, who search through literature, assessing various criteria for the inclusion of an annotation (such criteria vary by ontology). Since this is a laborious process, there are also many computational methods to annotate ontology terms automatically.

3.3.3. Examples of ontologies¶

3.3.3.1. Gene Ontology¶

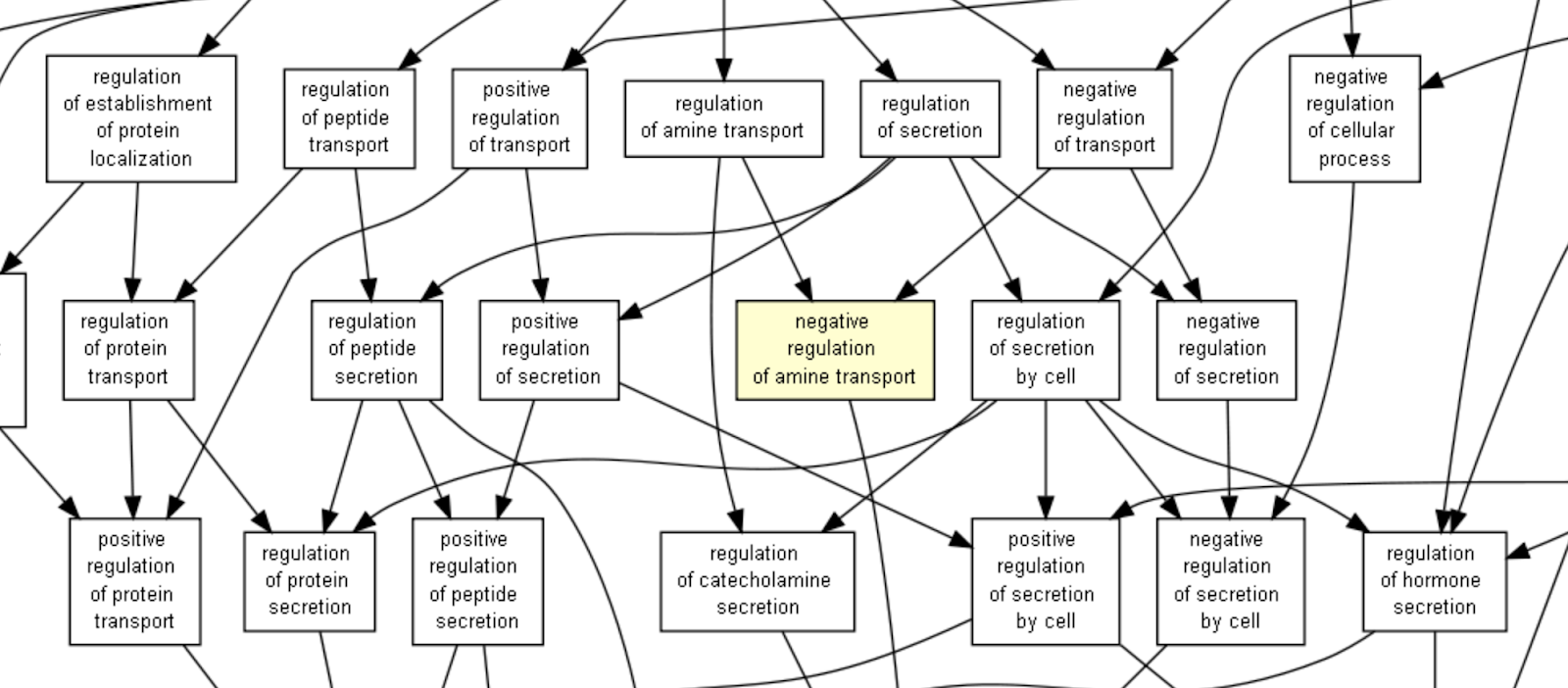

Fig. 3.4 A subsection of the Gene Ontology with arrows showing the existence of relationships (image generated using GOrilla[105])¶

The Gene Ontology (GO)[106] is one of the first biomedical ontologies, and continues to be one of the most popular. It is a collection of resources for cataloging the functions of gene products and designed for supporting the computational representation of biological systems[107]. It includes:

The standard gene ontology, which is a hierarchical set of terms describing functions.

The gene ontology annotations (GOA) database[108], which contains manual and computationally derived mappings from gene products to gene ontology terms.

Tools for using and updating these resources.

Gene Ontology terms: The Gene Ontology defines the “universe” of possible functions a gene might have (in any species), while the functions of particular genes are captured as annotations in the GOA database[107].

The terms in the GO ontology are subdivided into three types (molecular function, biological process, and cellular component), meaning that GO is actually a collection of three ontologies[106]. Gene products in GO are assumed to carry out molecular-level process or activity (molecular function) in a specific location relative to the cell (cellular component), and this molecular process contributes to a larger biological objective (biological process)[107].

Molecular functions terms describe activities at the molecular level (i.e. that can be undertaken by individual gene product molecules) such as catalysis, transport, and binding.

Biological processes terms represent larger scale functions (requiring several molecules), such as regulation, or even behaviour - these stop short of representing biological pathways (GO does not include the types of relationships that would facilitate this).

Cellular component terms describe what part of the cellular anatomy a gene product is part of, e.g. intracellular organelle, ribosome, or cell surface.

The terms in these three sub-ontologies are related to one another by relations, the most common are is_a (i.e. is a subtype of); part_of; has_part; regulates, negatively_regulates and positively_regulates.

Gene Ontology Annotations: Annotations in the GOA database are annotations between GO terms and gene products (proteins, protein complexes or RNA). The annotations include integration to the Uniprot protein function annotations across many species, which have been connected to the controlled vocabulary of GO by skilled biocurators, as well as electronically generated annotations. Evidence codes are provided for annotations which label whether annotations were verified by experts, as well as what type of experimental or computational evidence there is for an annotation. GOA also link to the supporting publications for the experimental annotations.

3.3.3.2. Uberon Ontology¶

Uberon is a cross-species anatomy ontology[109], whose terms represent body parts, organs, and tissues in a variety of animal species (mouse, xenopus, fly, zebrafish) and specific structures (Neuroscience Information Framework (NIF) Gross Anatomy, Edinburgh Human Developmental Anatomy). It is particularly strong in it’s integration to other ontologies, including anatomy ontologies for individual species, the Gene Ontology, Cell Ontology, phenotype ontologies (e.g. mammalian phenotype, human phenotype), the Experimental Factor Ontology (EFO), etc.

3.3.3.3. Other Ontologies¶

There are many other ontologies which aim to catalogue other aspects of biological experiments and knowledge. Other ontologies which are used in this thesis include:

The Cell Ontology[110] (

CL) describes cross-species cell types (from prokaryotes to mammals, but excluding plants). Example relationship: Osteocyteis_aBone Cellis_aAnimal Cell.The Disease Ontology[111] (

DO) describes human disease. Example relationship: Blastomais_aCell-type Canceris_aCancer.Human Phenotype Ontology[112] (

HP) describes “human phenotypic abnormalities encountered in human disease”. Example relationship: Motor Seizureis_aSeizureis_aAbnormal Motor System Physiology.The Experimental Factor Ontology[113] (

EFO) describes experimental setups common to the EBI databases. It is well-integrated with CL, Uberon, and ChEBI (chemical compound ontology). Example relationship: RNA Extraction Protocolis_aNucleic Acid Extraction Protocolis_aExtraction protocol.

3.3.4. Why are ontologies useful?¶

Ontologies can be used by researchers to investigate specific genes, tissues, functions of interest, or more generally to get a big-picture viewpoint on large groups of such entities. With logical reasoning, we can generate inferred relationships between distantly related terms in ontologies, for example \(is\_a \cdot part\_of \implies part\_of\). This allows us to find and check relationships that are not in the ontology automatically.

Ontologies and particularly their annotations are varying degrees of incomplete, and this will have an impact on the results of any downstream use of them.

3.3.4.1. Term enrichment¶

Ontologies are often used to try to make sense of a list of genes that are found to be differentially expressed across different experimental conditions, or that are outputs from GWAS. In the context of GO, a term enrichment analysis can be carried out to see which GO terms are overrepresented (a.k.a. enriched) for a given group of genes, thus saying something about the function of the list of genes.

3.3.5. File formats¶

There are two major file formats in which ontologies are currently stored. The OBO format is a human-readable format, while the OWL format is more complex, but has more functionality, and for example can be queried using SPARQL (an SQL-like querying language).