Sequencing and microarrays

Contents

3.1. Sequencing and microarrays¶

Sequencing and microarrays are how we get measurements of DNA and RNA. We measure DNA so that we can understand what organisms genetic material is capable of doing: and understand what the differences between different species and individuals are. These measures of DNA can tell us (among other things) what proteins it is possible to make. If we think of genes as a collection of blueprints, then one major reason that we measure RNA to tell us how much each blueprint is in production.

3.1.1. Sequencing¶

Sequencing technologies are used to read strings of DNA or RNA: this can be done de novo, i.e. even when we don’t know the sequences ahead of time. At one time, we might wish to sequence anything from one gene to the entire genome. No sequencing technology can read whole chromosomes end to end, however, all work by reading shorter lengths of DNA (called reads).

In most sequencing technologies (e.g. Sanger, Illumina), in order for the different nucleotides to be detected (by human sight or using a sensor), DNA is first prepared such that different nucleotides bond to different visible markers, e.g. different coloured dyes or fluorescent markers.

From the late 1970’s until the mid 2000s, Sanger sequencing was the most popular sequencing technology, although it underwent various improvements over this timescale. In Sanger sequencing (and other first-generation methods), reads of around 800bp are sequenced, one at a time, using electrophoresis. The human genome project sequenced the first human genome using this method[19], and it’s still used in some circumstances, for example validating next generation sequencing.

Second, or next generation sequencing (NGS), also referred to as high-throughput sequencing, is a catch-all term for the faster and cheaper sequencing technologies which replaced the previously used Sanger sequencing. A feature that is common to NGS methods is that many shorter reads (around 100bp, exact numbers depending on the specific technology) are sequenced in parallel. The process is massively parallel: millions to billions of short sequences can be read at a time. This is a huge factor in making NGS much faster (and therefore cheaper) than Sanger sequencing. In turn, this speed and cheapness means that more repeats can be sequenced, increasing the overall accuracy of NGS over Sanger (despite the accuracy of each individual read being generally lower).

NGS can be used for sequencing either DNA or RNA (known as RNA-seq when applied to the whole transcriptome). While (NGS) DNA-sequencing and RNA-seq can use the same underlying NGS technologies, there exist some differences, e.g. RNA is reverse-transcribed into strands of complementary DNA, before being sequenced, since sequencing DNA is currently easier than sequencing RNA.

There are now also third generation sequencing technologies that allow much longer reads to be sequenced, e.g. nanopore technology.

3.1.1.1. Capped Analysis of Gene Expression¶

Capped Analysis of Gene Expression (CAGE) is a NGS transcript expression technique which measures very small (27 nucleotide) segments (called tags) from the start (5’ end) of mRNA. These tags are mapped to genes based on their distance to the gene in bp. The upside of this approach is that these short tags can be used to identify the transcription start sites (TSS) of RNA transcripts. The downside is that it can only be used to measure mRNA (mature messenger RNA). CAGE is used extensively in the FANTOM research projects, such as FANTOM5 whose data is used in Section 5 and Section 7.

3.1.2. Alignment and assembly¶

Whichever technology is used, DNA and RNA is sequenced in small sections. This means that reads must then be aligned to an existing sequence (e.g. reference genome, known gene, or transcript), to allows us to know where on the genome (which chromosome and position on that chromosome) the read came from.

If an existing sequence does not yet exist, we say that we are sequencing de novo. In this case, reads are aligned with one another, as illustrated in Fig. 3.1 so that they can be assembled into a new sequence.

In both cases, alignment requires the reads to overlap, so longer and more numerous reads make these tasks easier.

Fig. 3.1 Image illustrating how reads of DNA are aligned with one anther to assemble genomes de novo.¶

The current estimate for raw sequencing inaccuracy of an individual NGS read is around 0.24%[52], meaning that on average one base pair will be incorrect for a 500bp read. Multiple repeats are therefore required to obtain a more accurate measurement of the assembled sequence, which is further necessary since there are many repeated sequences (perhaps over two thirds of the human genome[53]). The depth for a nucleotide is the number of reads that overlap that nucleotide. Similarly, the average depth of a sequence can be calculated.

After assembly, even in the most complete genomes, we are still left with some sequences that could not be placed, and some parts of the genome that we still don’t know about.

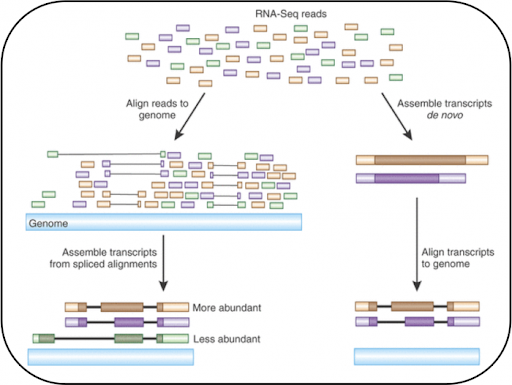

Fig. 3.2 Image showing how RNA-Seq reads are mapped to the genome (image from Advancing RNA-Seq Analysis [54]). RNA-seq is used much less often for de novo sequencing, and is generally mapped to a reference sequence.¶

Fig. 3.2 shows how alignment and assembly are used in the context of RNA sequencing.

3.1.3. Microarrays¶

Through the 1970s into the early 2000s, DNA arrays/microarrays developed alongside sequencing as a way of measuring the presence of previously sequenced DNA in new samples. These arrays contain pre-chosen fragments of DNA (probes) arranged in spots, with each spot containing many copies of the probe, on a solid surface, e.g. a glass, silicon or plastic chip. The probes consist of single strands of DNA, and arrays operate on the principle that the complementary DNA from the sample will bind tightly to it.

These arrays were originally macro-sized, one of the first being 26 × 38 cm and containing 144 probes[55], but are now on small chips, which can contain up to millions of probes. Different chips will contain different probes and therefore measure the presence of different sequences.

Arrays were extremely popular for measuring gene expression, but this technology has largely been superseded by the more accurate and comprehensive RNA-seq. DNA Microarrays are still commonly used by companies like 23andMe for genotyping an individual.